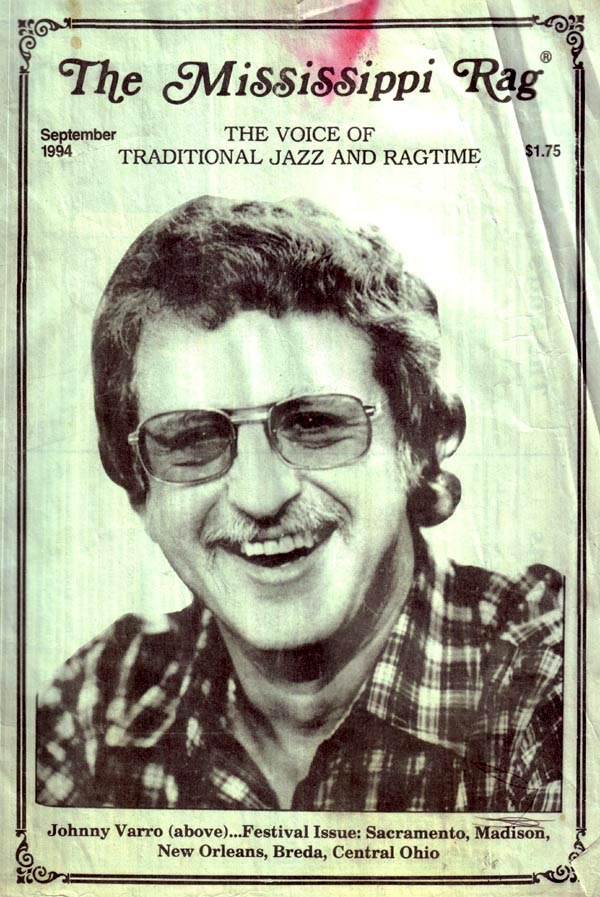

Johnny Varro, Cover, The Mississippi Rag, September 1994 |

| By Warren Vaché, Sr., extract from The Mississippi Rag, September 1994, pp. 1-8 |

A Visit With Johnny Varro

Johnny Varro, one of the finest in the current crop of Jazz pianists, has waited a long time for the recognition and appreciation that are his due. His career began when he was still in his teens when - as an exceptionally talented youngster - he was able to hold his own sitting in with the likes of Bobby Hackett and other big guns who made up the star studded groups playing at Manhattan's Central Plaza and Stuyvesant Casino in the late '40s. He went on to work Nick's in the Village, toured with Bobby Hackett and Pee Wee Erwin and, in general has been around on the jazz scene ever since - except for a period with the Army in Korea - but only now is he getting the exposure on records and in concerts that he merits.

Unlike the jazz musicians of a slightly older generation, Johnny, born January 11, 1930, was too late to take part in the era of the big bands. He started playing jazz in small groups and has managed to build a career and an excellent reputation based on that experience.

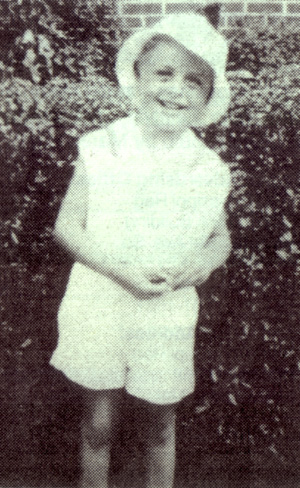

Johnny Varro, age 4, before he left Brooklyn. |

A Brooklyn boy, he paints a vivid picture of growing up in the Bensonhurst section in just a few words: "Until I was ten, I wasn't aware of too much music going around. I was busy competing with the rest of the kids in the neighborhood."

This began to change when his mother, who played "a little piano," gave him a couple of lessons and then, reasoning that since they owned a piano they might as well use it, she insisted he take lessons from a lady down the street who was a retired concert pianist and taught classical piano.

Varro recalls, "She was a marvelous teacher. And lessons cost a dollar a week. A dollar every Sunday morning when I took my lesson, and this went on for several years.

"It came very easy. I remember that in the beginning I kept going ahead of the lesson. I'd finish the lesson and then go on to the next couple of pages. I was anxious to get moving - to know more about the piano. This all went on for three or four years - long before my interest in jazz.

"Then one day my dad came home with a pair of Commodore records. One featured a trio - Jess Stacy, Bud Freeman, and George Wettling - playing 'Exactly Like You' and 'The Blue Room' and the other Eddie Condon's band with Joe Bushkin on piano doing `Ballin' The Jack' and 'Ain't Gonna Give Nobody None of My Jelly-Roll.' I heard these, and I realized that this was something different from anything I had heard before - and I couldn't get too much of it.

"My dad also brought home a couple of books. One of them was the Winn method book, How to Play Ragtime Breaks and Endings. It also explained other things to help you play jazz music, and in the back of the book it had chords. And for the first time I realized what chords were. I had already started fooling around with popular music - sheet music - but I really didn't understand what those funny little letters and numbers were above the melody lines. What's C7? What does that mean? The book helped me with that.

"My teacher was classically oriented, and she didn't give me much in the way of theory. I had to do that on my own. It also helped when my dad brought home some transcribed piano solos by Teddy Wilson. Also some by Jess Stacy and Art Tatum. He used to play clarinet but didn't pursue it, but he had the instincts for jazz and he loved it. And he was very instrumental in getting me interested in it.

"My father's name is Frank and he was born in Philadelphia. My mother is Josephine - 'Jo' - and she was born in New York City."

The records and the books his father brought home became important working tools for Johnny.

"I took those Teddy Wilson books to transcribe and I'd look up what he did with a C7th, or what Jess did with various chords, and apply it to the sheet music I had. I'd write it in very carefully in pencil until I got to memorize the abilities for each chord - what you could do with each situation."

It appears that during this period of growing up he was somewhat of a lone wolf. As he puts it, "I was not a socializer," and in spite of his intense interest in music he took no part of musical activity in school.

"I heard that school band, and it was so out of tune that I didn't want to get involved with it. It was probably a bit pompous on my part, but I felt I was beyond that stage. I didn't need it."

As a matter-of-fact, he didn't. Still in school, circumstances and a lucky break had already channeled him into much better things. He was performing at a professional level. And, as is often the case in such things, it all started very casually.

"When I was fourteen or fifteen years old, a buddy of mine in high school who knew I was interested in jazz and playing some, came up to me one day and said, 'I was talking to my brother about you, and he says he can stump you on piano players - that you can't tell the difference between Teddy and Jess and Mel Powell and all those guys.'

"By this time I had a bit of a record collection. I'd take my money into the Commodore Music Shop - all of a dollar and three cents - play a whole bunch of records, and come home with one. Jack Crystal was marvelous to me. He turned out to be a good friend. And Lou Blum. Both guys at Commodore were really nice. I remember one day I was buying a Bud Freeman record, and Jack Crystal told me, nodding in the direction of an impeccably dressed man - top coat with a velvet collar and a Homburg hat - who was checking through records, `There's Bud Freeman. Why don't you go over and talk to him?'

"So I went over and spoke to him, told him I was an admirer and a fan, and that some day hoped to be able to play with him. Fortunately, that did come true later on. I used to hang around the Commodore Music Shop a lot.

"When my friend told me about his brother's challenge, I didn't hesitate. 'I'll take him on, I said, and I went over to their house one Saturday afternoon.

"He had a huge collection of records - all 78s in those days - on shelves against one wall. It's a wonder the floor didn't collapse, and he was on the second floor. We went through a little bit of a blindfold test, and I got him every time - especially on Jess and Teddy. Mel Powell was a little tough for me then, although not any more. Anyway- we developed a friendship. His name was Tom Stagno, and he began taking me down to the Central Plaza and the Stuyvesant Casino. At that time Bob Maltz was running the Stuyvesant Casino, and I got to meet Joe Sullivan, Willie the Lion Smith - all through this friend of mine - and Bobby Hackett. He introduced me to all these players - all the guys who were around at that time."

One step led to another, and before long Johnny was sitting in on some of the sessions, half scared to death, but thrilled to the bone, and delighted to be associating with the men he had come to admire so greatly. As it turned out, he must have performed quite well, because the next step came along logically but also almost casually.

"One day Bob Maltz told me he was going to put my name on the card - that is, the cards they used to send out to the fans to let them know who was in the next week's program. 'I can't pay you,' he told me, 'but I'll put your name on the card.' I remember the group I played with that first night - Max Kaminsky, Tony Parenti - I think Charlie Costaldo was on trombone, Harlow Atwood on bass, Baby Dodds, drums. As the night progressed, though, it started going well and my main worry eased off. I knew all the tunes. That was my main concern - whether I would know all the tunes. And just about the time I decided I didn't have to worry about that any more, all of a sudden Chippie Hill - Bertha 'Chippie' Hill - came in. And she got up on the bandstand - a very imposing figure - and I thought, 'Oh, my God, now what?' I was still a kid, not quite eighteen, and I was scared to death.

"But it turned out that she sang some tunes I knew, most of the stuff was blues, anyway, so we got along OK It was quite a night. Had my whole family there, and everything."

Although Johnny, as a kid from Brooklyn, didn't travel in the same environs, he was aware of the other young jazz players coming along at that time- especially those in the so-called Scarsdale Gang - Bob Wilber, Dick Wellstood, Johnny Glasel. "All those kids from Scarsdale. I was kind of from left field-the kid from Brooklyn-and I didn't get to meet those guys then. Later on, of course, our paths crossed, but at that time I felt left out in the cold. But I knew Tom Stagno, and he introduced me to a lot of people. Then Central Plaza started, and I used to hang out there a lot and got to know a lot of people - Jack Crystal, Willie the Lion, and whoever else was there. Bobby Hackett and Wild Bill Davison were in and out of there all the time.

"So I just kept gigging, learning tunes, trying to improve my style and, above all, listening. And I was starting to get paid. Jack Crystal paid me. Looking back, I was very fortunate. I was very lucky that I happened to be part of that scene. Each weekend they'd hire four piano players, two for Friday and two for Saturday, and I'd get at least one of those spots. This kept me in the limelight, and it enabled me to meet the right people.

"Central Plaza was a big wedding hall located on 6th Street and Second Avenue, downtown on the lower East Side. Stuyvesant Casino, also a wedding hall, was about a block and a half north around 8th Street. Bob Maltz originally started the one at Stuyvesant Casino, I think, then he switched to the Central Plaza. Somebody else took over the Stuyvesant. Central Plaza became the place where I played the most. Jack Crystal ran it, and it was a happier situation. For one thing, you didn't have to wrestle for your money. Jack Crystal was a very kind, generous, and sweet man, who didn't mind giving a young fellow a break. And the players I met there! James P. Johnson and Cliff Jackson were always hanging around. And Sammy Price. All piano players. The horn men included Lips Page, Pete Brown, Sandy Williams, Lawrence Brown - I played with Big Sid Catlett. People ask me about those days, and when I say I played with Big Sid, they seem to marvel at the idea and repeat, `You played with Big Sid Catlett!' Well, I did."

Something of the magic and the wonder of those days is conveyed in Johnny's voice as he tries to describe them. You can almost visualize' the excitement and enthusiasm he experienced at taking part in a segment of jazz history, and the inner awe and amazement at being so lucky.

The Varro saga is unusual for a couple of reasons. For one thing, accidentally or otherwise, his timing was just right. His playing ability matured just at the right moment to allow him to fit into the jazz activity taking place in New York which, in itself, was a new departure for the music. Small-band jazz - mostly of the free-swinging, pick-up group variety- was enjoying a post-war vogue that for a few short years was able to fill the void created by the demise of the big bands. Youngsters like Johnny moved right in to playing small-group jazz without serving an apprenticeship in a big band. Johnny even managed to avoid playing in any school orchestras.

"I never did. The first time I played with a big band was much later on. I enjoyed it tremendously. But at that point I went right into playing jazz."

He also made himself visible and available, frequenting places like Nick's and Condon's, and sitting in at any opportunity.

"Mainly my education really happened at Jimmy Ryan's on 52nd Street. My buddy took good care of me. I'd be standing there, just listening, and all at once I'd hear Joe Sullivan say, `We have a fine young piano player here tonight, Johnny Varro, who is going to sit in for the next number.' Since my buddy never let me know in advance what he intended to do, these announcements were always a surprise and I was always scared, but at the same time I was happy to do it."

It was almost an idyllic period in Johnny's life. He was playing the kind of music he loved, working and associating with musicians he respected and revered, and in reverse, enjoying their friendship and encouragement. And, like all good things, it ended.

"The Korean War started, and in 1951 I was drafted. I spent about eight or nine months in radio school at Camp Gordon, Georgia. My ear got me into radio. Then I went to Korea for a year. I wasn't with Special Services, but I volunteered to help with some shows, and wrote a little music for them. At that point I started to do a little writing. I never studied it, just did it the way I thought it should be. I understood what the instruments did, and how to transpose for each instrument. I made mistakes, of course, but I learned from them. I was a radio operator in the Signal Corps. Then after awhile in Korea I got into cryptography, I was there for just about a year - from March of 1952 to February of 1953.

"Then I came back, was released from the service, and didn't know what to do with myself. Then one day I got a phone call from Bobby Hackett.

"He asked me a few polite things, like `How are you?' and `How did you like the Army?' and then said, `What are you doing these days?'

"Nothin'!' I told him, and I was really in the doldrums. `I'm just sittin' around wondering what to do with the rest of my life.' "Well, I've got something for you. I'm taking a quartet to Ohio. We're going to do some touring, but the Grandview Inn will be one of our stops. I want you to come with me. I think you should make it.'

"It was just what the doctor ordered, but this time I was really scared. I told him, 'Jeez, Bobby, I haven't played for so long - I don't know - '

"Well, meet me at Lou Terassi's on West 47th. You know where it is. Get there in an hour or so, and we'll talk things over.'

"Jeez. I was all churned up inside. This could be exactly what I wanted. On the other hand, after all that time away from jazz - I got dressed in a hurry, took the trolley and the trains, and met Bobby at Terassi's.

"After we shook hands, he said, `Play something for me.' I sat down and played a couple of things, and then Leo Guanieri happened to be in the place - I think he was working there that night - and he sat in and played some bass behind me. I appreciated the support. And after playing about fifteen minutes, Bobby came off and told me, 'I think you should go with me.'

"I was delighted - but still scared. 'Are you sure, Bobby?' My inadequacies and insecurity were showing again, but Bobby, in that calm, quiet, confident way he had, just shook his head yes, and said, 'Yeah. I can help you.'"

So Johnny joined drummer Buzzy Drootin and bassist Billy Goodall, and went to Ohio with Bobby Hackett.

Bobby Hackett's Quartet at the Grandview Inn, Columbus, Ohio, in 1953. From left: Johnny Varro, Bobby Hackett, Buzzy Drootin, and Billy Goodall. |

"It was great, and just as he said, he was a big help to me. I'd play a chord and he'd correct me. 'No, use a C7th there,' or 'Use a Db suspension here.' And he was able to do it while was playing - call it out between phrases - and it was wonderful. I enjoyed the sessions, and I learned a lot. We became good friends. Later on I worked with him quite a bit. The tour took place around May of 1953, and after we came back I sat around again for about two months."

This time it was guitarist Nappy Lamare to the rescue. He was just in from the Coast with a trumpet player, Rico Vallesi.

"Rico, like Bobby Hackett, was from Providence, Rhode Island, and he emulated Bobby. Tried to play like him and did pretty well, too. Great sound! So I went with Nappy, and in the band we had Eddie Phyfe on drums, Nappy, Rico, and Albert Nicholas on clarinet.

"It was the summer of '53, and the tour started in 'Toronto, Canada, and then we went to the Grandview Inn. We played a lot of places in the Midwest - some of them you never heard of - and we also played The Red Arrow in Stickney, Illinois. This is a little place outside of Chicago, and they had quite a bit of jazz there back in the '50s. I don't know how long this lasted, but we played there once. It was a good tour, and went on for about five months. I saved enough money to buy my first car, a 1950 Ford."

Back in Brooklyn again, Johnny worked local dates and whatever came along, and then in 1954 he heard via the grapevine that Phil Napoleon, a fixture with his band at Nick's, was looking for a piano player.

"I went in on a Sunday afternoon and played a set with him, and he hired me on the spot. The next thing I knew I was working at Nick's with Phil Napoleon."

Besides trumpet-playing Phil, the band included Gail Curtis on clarinet, a former Dorseyite; Harry DeVito, trombone; drummer Lew Koppelman, and Pete Rogers on bass.

"We did a lot of things with that band. Television stuff. The Kate Smith Show, the Paul Whiteman Show. Of course, in those days it was all live TV, where anything could happen - and did. Then, when the Dorsey Brothers took over with a summer replacement program for the Jackie Gleason Show called `America's Greatest Bands,' or something like that, I played on it a couple of times. They used four bands each week, fifteen-minute segments for each, and I played with Art Mooney's band. That was the first big band I ever played in. He did a feature that was a tribute to great bandleaders and I took the part of Eddy Duchin. They arranged to have my silhouette projected against the back wall, and I played Chopin's 'Nocturne.' I think it was his theme song. Nappy was in the band. In fact, he got me on it.

"We also did a segment on the show with the Phil Napoleon regular group. It was great.

"Every Friday night Harry Woods would come in to Nick's with Willard Robison - they were good buddies. They'd come in and when we started work at 9 o'clock these two guys were already deep in their cups, feeling no pain. Then, around 11 o'clock they would have ordered their dinners - two of Nick's nice juicy steaks - and they'd both be fast asleep, so the steaks would just sit there. Now, don't forget, these two guys were legends in the song-writing business. Nobody was about to wake them up or tell them to get out. They'd just leave them alone and the steaks would get cold. Finally, at the end of the night, one of us would wrap a steak up and take it 'home for the dog.' I enjoyed several.

"One evening they stayed pretty sober, so Phil Napoleon decided to invite Willard up to the bandstand to sing and play a couple of his tunes. And I should point out that this was pretty unusual in itself, because the format at Nick's was pretty cut-and-dried and hardly ever varied. However, Willard came up and did his `Old Folks,' and a couple of other songs, which was fine, but when he finished Phil was practically obligated to call on Harry Woods.

"I tried to warn him not to, because I knew that Harry was missing his left hand. He only had a stump, with a little button on it, but Phil went ahead and announced, 'We have another famous composer in the house, Harry Woods.' And Harry stood up eagerly, climbed on the bandstand and sat down at the piano. 'This, I gotta see,' I said to myself, but he played. He played in Gb so he could hit the black keys with that little nub. And he did quite well."

Johnny continued to work Nick's with Phil. Then Napoleon left to move to Florida, and Pee Wee Erwin took over the band. Johnny stayed on, and clarinetist Kenny Davern joined.

"Up to this point I had always been the youngest guy in every band I played in. But now Kenny was the youngest. I've got five years on Kenny. It was the same band, with Harry DeVito on trombone, but the rhythm section kept changing. Lew Koppelman left and Phil Failla came in on drums. Pete Rogers was still the bass player, though.

"Pee Wee was a good friend," Johnny states with firm conviction. "He was concerned about the people he played with. I had a bit of a drinking problem, and we had long talks about it. This might seem a little odd, because Pee Wee had his own problem, but he was a periodic drinker. He'd go off on binges. He'd be dry for a long time and then he'd fall off the wagon and then the well known product would hit the fan. But I was constant. I mean, I just kept on going."

The association with Erwin continued. In 1956 Pee Wee put a band together to play a Long Island location, The Melody Lounge. It included Johnny and Kenny Davern, a trombonist from Illinois, Sam Moore, Bobby Donaldson on drums, and bassist Jim Thorpe. The unit immediately displayed merit, so Pee Wee arranged a series of dates and took the unit on the road, at which point Tony Spargo replaced Donaldson.

All went reasonably well until the band moved into the Grandview Inn in Columbus for a four-week run. They opened on May 14th and played a very successful engagement until May 30th, Pee Wee's birthday. The always sociable Pee Wee was invited to a cook-out that day by well-meaning friends, but they made the mistake of leaving a full bottle of whisky on the counter in the kitchen. Pee Wee drained the bottle and passed out.

"I remember the situation," Johnny states with a sober nod. "Kenny and I both went looking for him. He didn't show up for the job, so after it was over we went to the hotel where we were staying, and checked with the hotel clerk. He told us a horrendous story. Those were the days before air conditioning, and the hotel had this huge fan - it stood about twelve or fifteen feet high - in the lobby, and Pee Wee fell into it. The fan then fell on top of him, and he was lucky he wasn't decapitated, or killed, or lost something or other. Then we went to Pee Wee's room and found him out cold on the floor. For Kenny it was the final straw. He sat down and wrote Pee Wee a note that he was quitting, and went back to New York. I stayed on, but Tony Spargo quit, too. Then Jim Thorpe left, although he sent in a replacement, and I took the opportunity for a vacation. Charlie Queener filled in for me. But Pee Wee had to do some fast reorganizing in order to fill the engagements he had booked. I was back in the band, though, when we opened at a club on Bourbon Street, New Orleans, called The Dream Room. Which, of course, is not there any more. Pete Fountain and A1 Hirt used to come and sit in.

"I don't know who the clarinet player was in that band. In fact, I don't remember much about anybody, because the personnel kept changing so frequently. It wasn't a very secure situation. But I stayed. I hung in there, mainly because I had just gotten married - to my first wife - so it was a honeymoon for me and a big, wonderful party."

In spite of the fact that Johnny Varro had been playing with famous musicians like Bobby Hackett, Phil Napoleon, Pee Wee Erwin, and others, all frequent and familiar faces in recording studios, up to this point he had never seen the inside of a recording studio. What's more, when the opportunity did come along to make records (for Enoch Light's "Grand Award" label) the band personnels were either not mentioned at all, or the names were all wrong. After waiting for so long to record, Johnny took this neglect to heart.

"We did a lot of those albums, and they'd screw up the names, and this really ticked me off. I couldn't help it. I'd yell, 'What the hell am I in this business for? I need all the help I can get, and look what they do to me!'

"It's too bad, because we need that exposure. Nowadays musicians get very little help from radio and TV, so records are more important than ever when you're trying to build a reputation."

As the '50s decade moved into its waning years, Johnny continued to work at Nick's. One summer neither Pee Wee Erwin or Phil Napoleon - for many years the standbys of the place - was available. This could have resulted in the loss of jobs for the musicians who worked with them, but after some fast thinking they approached Grace Rongetti with the idea of letting them form their own band.

"Actually it was made up of the same guys who played with Pee Wee and Phil - Kenny Davern, Harry DeVito, Phil Failla, and Pete Rogers - but with a different trumpet player, Tony Spare. Tony was from New Jersey and he was influenced a lot by Phil Napoleon - had the style down so things worked out pretty good. We called ourselves The Empire City Six, and we made several albums. One was for ABC-Paramount, and instead of letting us play our own things they wanted us to make an album of college songs. I did the research. 'Went to the library and looked up some of those adaptable songs like 'Anchors Aweigh,' and 'On Wisconsin,' 'I'm a Ramblin' Wreck from Georgia Tech,' 'Roar, Lion, Roar,' and arranged them for the band. It was my first attempt at arranging anything that would be as long lasting as a recording. And we did that, and in regard to names being spelled wrong on albums, Kenny Davern's name on that first album was listed as 'Lavern,' which shattered him. You can imagine!

"Then we did a second album for Hallmark Records, a rather obscure label, but we were able to do some of the songs we usually played. The album was called The Empire City Six In Dixie. The first one was The Empire City Six Salutes the Colleges. The cover had college flags all over it. ABC-Paramount was a pretty good label, and at first the album sold so well that they were giving us monthly reports on the sales. 'Oh, it's selling like hot cakes,' But when they came to realize that they might have to pay us residuals on the date, the sales reports fell off drastically. We didn't sell this, we didn't sell that.' And there was nothing we could do about it. They knew we were incapable of checking on them. Putting it politely, I think they shortchanged us.

"But, anyway, the band was working. We played some weekend dates at a jazz place in Trenton, N.J., called The Rendezvous, and we played outside gigs for colleges, and I think we were together for several summers. Then we disbanded."

At that point another door opened for Johnny. He got a phone call from Eddie Condon, who asked him to come into the club for a talk.

"So I went into the old joint, the one on 3rd Street, and we had a drink together. He said, 'I'd like you to come in. Ralph [Sutton] is finishing up playing intermissions, and I'd like you to come in and play duets with Buzzy Drootin on intermissions.'

"The regular band at the time was Wild Bill, Peanuts, Cutty, Gene Schroeder, George Wettling, and Leonard Gaskin, so I told him, `Sure. It's great company to be in.' So Buzzy and I started playing intermissions, and this lasted about six or eight months, and then the regular band went to England, and I became the house piano player with Buzzy on drums. They brought in Walter Page to play bass, with Jimmy McPartland, Pee Wee Russell, and Vic Dickenson in the front line. And, of course, on Tuesday nights they always had people like Bobby Hackett and Bud Freeman. That period at Condon's was one of the greatest times of my life. I got to meet more players and people, and it was a very impressive place for me to be. I loved Eddie. He was an inspiration in many ways, a great, unforgettable person.

"Some of the incidents are unforgettable too. One night it was late in the evening and some guy out of the audience came up to Wild Bill and made a big deal of reaching into his wallet for a bill, and requested we play `Muskrat Ramble,' or some other tune we didn't feel like playing. Then he laid a fifty-dollar bill on the old drum - an old tom-tom - they used as a coffee table and to hold ash trays, drinks, and such. Then the guy, acting very cocky, as though he had made a tremendous donation, turned to walk away. Bill looked at the fifty dollar bill, then at the guy's retreating back, and in a loud voice said, `Just a minute, you!' The man stopped and turned around with a surprised, `Yes?' and Bill, pointing to the money, went on, `Come back here and tell me how you expect us to divide fifty dollars between six musicians.' There was a long silence, and then the guy realized that every eye in the place was watching him, so he took out the wallet again and laid another ten on the drum.

"During intermissions we used to play cards a lot in the room downstairs, and Bud Freeman would come in and play with us. Bud always liked to govern the stakes of the game depending on how his luck was running. If he was doing well he'd make suggestions. 'Let's raise the stakes to five,' or ten or fifty, but Jimmy McPartland would always berate him. `Come on, man, these people are working musicians. They have families to support. You don't have anything to support except your saxophone!'

"When I first went to work at Condon's I was drinking a whisky called Corby's Reserve. I kept a bottle in my locker - one of the little wooden lockers we had in the downstairs room, where we could hang our coats. The bottle was easy to recognize because it had a picture of a parrot on it. Well, after the first set this particular evening I went down to the room, and as I walked in I saw Cutty Cutshall drinking from a bottle of Corby's Reserve. Now, I had just met him - said hello for the first time and really didn't know him, except by reputation, so I thought `Jeez, the guy took my bottle! He's drinking my whisky! But OK Since he's Cutty Cutshall it's OK'

"And then he offered me a drink. `Have some,' he said, and handed me the bottle. So, figuring I might as well have a drink of my own whisky, I took a slug, and then he took the bottle and put it away in his coat. Again I thought, `That's pretty nervy. How brazen can you get?' But then I had another thought. I went to my locker, reached in to check my coat, and there was my bottle. Feeling pretty small, I pulled it out, opened it, and offered it to Cutty. `Here, have some of mine.' We were the best of friends afterwards. Cutty was a sweet man. They were all nice guys in those days.

"It's sad to realize that most of them are gone, but I'm delighted that I had the chance to know these people. I was very fortunate to come up when I did in the music business, when these fellows were still alive. I got to meet and play with a lot of them, and to talk with them. People like Pee Wee Russell, for instance. We never really became great friends, but he was a great guy. When he wasn't working with the band he used to come into Condon's and sit at the end of the bar, and during intermissions I'd go over and talk with him. He usually brought along his little dog, a schnauzer. It had a little mustache like Pee Wee's. This one time he came in without the dog, so I asked, 'Where's Winky?' and he said, 'I'm mad at him. He let me down.'

" 'How can a dog let you down?' I wanted to know, and he told me a little story that has to be pure Pee Wee Russell material. It seems that whenever he got a couple of bucks ahead he'd stash it away under a rug in the apartment where he and his wife Mary lived. This time Winky saw him hide the money, dug it out, and took it to Mary. `We're not talking these days,' he wound up, looking very serious about it."

As before, all good things come to an end. Johnny still looks back with nostalgic pleasure on the Condon stint, but around the middle of 1958 it was over, not only for Johnny but for the 3rd Street saloon. "Yeah," Johnny sighs regretfully, "It was a great place. Had an atmosphere, you know. My dad used to take me there when I was sixteen. We'd sit up in the balcony and I'd look down and watch Joe Sullivan play piano. The good old days - no microphones."

Johnny's next stop was The Metropole, located on Broadway between 48th and 49th Streets, working in a trio with clarinetist Tony Parenti, and Phil Failla on drums.

"We started playing in the afternoon, working opposite another trio led by Louis Metcalf, with Freddy Washington on piano, and Zutty on drums. It made for a fun afternoon. There weren't too many people there - it was too early - and the money was just awful! But I was lucky because my afternoon would extend into the evenings. Marty Napoleon was playing there at night with Charlie Shavers and Coleman Hawkins, and Marty was getting a lot of better-paying jobs outside, especially on weekends, so he'd ask me to stay over and play the nighttime sessions. So I got to play with Coleman Hawkins and Charlie Shavers, with Mickey Sheen on drums, and Gene Ramey on bass."

Johnny still wasn't being called on to make records, even though it was a very active period for the Condon gang and the other musicians he was working with.

"I guess, as always, they were sticking to the big names. Gene Schroeder made a lot of records, so did Jess and Joe Bushkin. But there was quite a bit of jazz action during that period. The Metropole went on for years, and Eddie Condon opened up uptown in the Sutton Hotel, and The Embers was going, and the Roundtable. They even had a little room upstairs at The Metropole. I played there with Wild Bill, and I played with Bobby Hackett at The Embers. There was a lot going on then - a lot of clubs."

For some odd reason Johnny was still missing out on record dates. Bobby Hackett recorded with his group from The Embers . . . but Johnny wasn't with him at the time. "It's funny," he says, "but I seem to get lost in the cracks. To give another example, in 1956 Bobby called me for another road tour. We were going to the Blue Note in Chicago, with Vic Dickenson, Tommy Gwaltney on clarinet and vibes, Tony Hannon on drums, and John Dengler on bass sax and whatever other horns he decided to play.

"That was the band. Now, if you're familiar with the personnel of the band Bobby had at the Henry Hudson Hotel later, which also was recorded - Well, remember that tour with Pee Wee Erwin in '57? This is how it came about. The Hackett group finished up at the Blue Note and we played a couple of other spots, then came back to New York and there was nothing going on. So when Pee Wee called with the offer to tour, I took it. Then only a short time later Bobby landed the Henry Hudson job, which I would have been on had I stayed in town. So once again I fell through the cracks. But I am on one thing that I really appreciate.

"In 1961, I think it was, we got a call to do a film for the Goodyear people. I believe they called it an industrial film. Anyway, the leader was Eddie Condon, and we had Wild Bill, Peanuts, Cutty, Buzzy, and a bass player named Joe Williams. It was a real class production. We wore tux pants and white jackets. It was produced by Mike Bryan, and they made three films altogether. The other two are by Bobby Hackett and Duke Ellington. So I got on the Condon film, and it has been great. I've gotten a lot of compliments for it, and I've been to people's houses in Europe where when I walked in they were playing it. It has certainly made the rounds.

"You see, at that point Gene Schroeder had left Condon's to join the Dukes of Dixieland, so that opened the piano chair for me and I did a lot of traveling with Eddie."

Johnny is vague in his recollections of the late '50s and early '60s, other than knowing he played in most of the jazz clubs that were active at that time, The Embers, the Roundtable, and a lot of the work was with Bobby Hackett, but he also admits, "Those were my drinking days. I was in and out of a lot of groups. I was still missing out on recording sessions - for instance, when I first went with Bobby Hackett he had just made four or six sides for Columbia. But I did do one thing with Eddie Condon, and Bobby was on it, too. Again it was for Columbia, and we made several sides, but what they wound up doing for the album was to take one track from several sessions and put them on one record. Duke Ellington's band is on it. But, of all the sides the Condon bunch made, they put `Tiger Rag' on the record. I don't remember the name of the album."

Taking Gene Schroeder's place with Condon, Johnny began a lot of traveling. "We played all over. We went to Chicago and played the Colonial Tavern. Buck Clayton was in the band then. We went to Indianapolis where we played for the Race Week. We must have played five or six parties each of the three years we were there, '62,'64, and '66. We had a pretty set group, but from time-to-time we had different horn men. Billy Butterfield, Lou McGarity, and Peanuts, and Buzzy did a lot of the work. Other times we had Yank Lawson and Bobby Hackett. I never lost the thrill of playing with those guys. I'd think to myself, 'Here I am playing with Bobby Hackett,' or Lou McGarity, or Cutty Cutshall. I never got over that.

"I recall another time while I was at The Metropole. Jonah Jones, long before he made his big hit with his quartet thing, put together a group with Benny Green, Coleman Hawkins, Jo Jones or Manzie Johnson on drums, various bass players, and me. All those heavyweights and me - the great white hope! But Jonah liked me, and was real nice to me. We played a lot of college dates, but I don't remember where or when. It was around 1957, because I recall we were at The Metropole when they broadcast that big TV special, The Sound of Jazz. They recruited a whole bunch of guys from The Metropole to play that show, and a bunch of subs went into The Metropole to fill in for them. If you weren't playing, you ran across the street to The Copper Rail to watch the guys playing. After all, they were friends of ours, people we knew, and what an honor to be able to work with them. So much happened in those days. What an exciting period.

"There are a lot of stories, I guess, but one of the funniest I sent to Bill Crow. Since then a lot of people have claimed it, but it actually happened to Buzzy Drootin and me. When we were playing intermissions at Condon's, the place was filled with Italian waiters. One in particular, named Ambrose, used to destroy the English language. One night he came over to me and Buzzy and said, `I have a requesta for you to play, "Coma Rain, or Coma Shine" - either one.' I've told that story a number of times, and now I hear it coming back to me. I get arguments when I say it was me. Nah, it wasn't you!' But it was me."

Johnny continued to do a lot of traveling with Eddie Condon well into the '60s. Then he went with Edmond Hall's quartet into the second Condon's in the Sutton Hotel on 55th Street and 2nd Avenue.

"And that lasted for months and months and months..." But once again Johnny's timing was off. Edmond Hall recorded extensively, but most of the activity took place before Johnny joined the quartet, and no recordings were made while he was in it. The other two members were Bucky Calabrese on bass, and John Marshall on drums.

"Edmond was a very kind man, very nice to me. I was going through a drinking problem at the time. We didn't record, but we did travel to Odessa, Texas, before they started the jazz party. Doc Fulcher brought us in as a special attraction. I played a lot of gigs with Ed. Wherever he played I was his piano player for three or four years.

Johnny Varro was stylishly groomed when he played as one of the Dukes of Dixieland at a 1967 gig at Earthquake McGoon's in San Francisco. |

"Then in 1964 I finally saw the light and stopped drinking, and went to Florida. Phil Napoleon gave me a call. 'Why don't you come on down here? I've got a nice job at the Roney Plaza Hotel, and we're doing the Jackie Gleason show.'

"Which reminds me. Back in 1955 and '56 we did the warm-ups for The Honeymooners, those half-hour segments that were so popular. We played while the audience came in. Play about a half hour for the people, warm them up, and then play during set changes and the commercial breaks. And the front row was for our seating. We'd sit down and then they'd film The Honeymooners. You can hear us laughing. When they show those re-runs on TV, I can still hear Phil laughing and certain chucklings by the other guys in the band. That was the regular Phil Napoleon band. Kenny Davern came in with us the second year.

"Getting back to 1965, Phil's phone call was more than welcome. It was January and snowing in New York and there was very little work. By then The Metropole had turned to go-go dancers, most of the other clubs had closed, and rock and roll had taken over. So I cleaned up my act - stopped drinking - and went down to Miami Beach to join Phil. He was back doing warm-ups for Jackie Gleason - for the big hour-long show they called The American Scene Magazine, with Art Carney and Sheila McRae instead of Audrey Meadows.

"It was a totally different band than the one in New York. Bill Burns was on clarinet, Ed Hubble on trombone, and Lew Koppelman on drums, and the bass player was Al Matucci. These guys at the time were all Floridians. The Florida move was a good one for me. The trouble was it was probably too good and lasted too long. I eventually landed a job that lasted nine years with a trio of my own, and it got so comfortable . . . We worked at the Montmarte Hotel in Miami Beach. In the beginning I had Don McLean with me on drums, he had been in the Billy Maxsted band at Nick's, and A1 Matucci on bass. The job lasted nine years, which was about five years too long. I was making good money, buying a house and starting a family, but my career just kind of sat there and people forget, you know.

Billy Butterfield's Quartet at the Escape Hotel in Ft. Lauderdale, Fla., including the musicians from the augmented Grand Opening band. From left, rear: Johnny Varro, Eddie Condon, Chubby Jackson, Bob Wilber, Yank Lawson, Don MacLean, Vernon Brown. Front row: from keft: Unidentified, Wally Cirillo, unidentified, Billy Butterfield, Ray Tucker, and Deane Kincaide. |

"Then I got a call from the Dukes of Dixieland, and I went with them. Freddie had died, so it was just Frank Assunto. Lee Gifford was on trombone, who had been with Billy Maxsted's band, Jerry Fuller, clarinet, Dan Shapira on bass, and Barrett Deems on drums, so it was a pretty good band. I mean, it was a swinging band. And we toured. We traveled all over Florida, and then we went to the Far East for a month, hitting about ten countries. We played Bangkok, Korea, Japan a lot, Singapore, Manila ... I was with them a year and three months. That tour ended for me in Fort Lauderdale, because I had given them notice I intended to get off there. They kept going but I had enough travel."

So Johnny went back to Miami Beach, where he lined up the long-lasting job at the Montmarte Hotel.

"We were able to play some dance music early in the evening when the people started to come in, but by 9 o'clock it was show time and we had to play for the acts. This helped my reading chops, and I also began to do some 'arranging. I remember the song `I've Gotta Be Me' was very popular at the time, and I must have made 25 arrangements of it for singers.

"Well, it became time for this thing to end. Miami Beach was falling apart anyway. The condominiums had taken over and most of the tourists became residents, so business fell off. They started cutting down expenses in the hotels, and from six nights a week they wanted three - it was time to leave.

"The choice was either to return to the New York area or try L.A. A couple of my friends had gone out there and they said it was pretty good, but I decided to try New York first. For awhile I enjoyed it, even though I just gigged and clubbed around and nothing looked certain. But I subbed a lot at the new Eddie Condon's on West 54th Street, which meant that I have played all three of the clubs with that name, and it was nice. I worked with a lot of good people. I did a thing with Vince Giordano, and the trumpet section consisted of Pee Wee Erwin and Jimmy Maxwell, or Chris Griffin and Bernie Privin. You know, those guys really knew how to interpret the music that Vinnie was playing, so playing with the band was a lot of fun. At that time it included a lot of good players. Bobby Pring was on trombone, Clarence Hutchenrider played alto and clarinet, and Artie Baker was in it, too.

"Mentioning these names reminds me of a job back in the '60s. Miff Mole had connections with a place in Bellmore, Long Island, called The Mandalay, and either the first or last Sunday of the month, he put together a jazz group there. I still have a card from the place that lists the musicians who played there from time to time, and the list is remarkable, from Bobby Hackett to Charlie Shavers, and just about every musician who was alive in the area at that time. The card also shows that you could buy a hamburger for thirty-five cents, or a hot dog. I also recall that poor Miff didn't even own a heavy coat in those days. In the dead of winter he'd be wearing a regular jacket. We took up a collection and bought him a coat."

After trying New York for a reasonable period, Johnny decided to try Los Angeles, and for once in his life the timing was just right. Almost immediately he crossed paths with Johnny Guarnieri, whom he had met years before in New York.

"He had a steady job in a place called The Tail O' The Cock, a steak house, and he told me, 'I'm taking off for two-and-a-half months to make my annual road tour. I go to different places and play for awhile. Do you want to come in here for me while I'm gone?'

"Did I! I walked right into a nice two-and-a-half month gig, and during that time I developed a following of my own. The place was located in the San Fernando Valley. You worked at a piano bar. Johnny had made a lot of friends, people who would collect around the bar, and he'd talk about music, tell them stories about Fats Waller, things like that. And I fell right into it. People got to know me, and I started getting outside bookings. They have a lot of jazz clubs in Los Angeles. It's a huge city, and it was a good place to live when I went there in 1979. I eventually lined up a steady job of my own at a place called Gatsby's. It was owned by Bill Rosen and Helen Grayco. You may remember, she was married to Spike Jones and sang with his band. I worked there for about five years, which was maybe a little too long for that gig, too, but it was a nice one and helped me to buy a house.

"Around this time I figured I was long overdue to make some recordings, so I talked to a man named Dan Grant, who had put together a couple of concerts. One of them was with a quartet including Eddie Miller, Gene Estes, and Ray Leatherwood, and we got such an enthusiastic response that I convinced Dan Grant into recording a repeat session. It turned out to be a good album called Street of Dreams. It's on the Magnagraphic label, which you probably never heard of before. That's reasonable. Hey, when the big outfits won't record you, you do the next best thing and start your own company. As it is, the first album went so well that Dan decided to produce another. This time, instead of Eddie Miller we had Chuck Hedges, and the album is called The Square Roots of Jazz. The rest of the group is the same, Gene Estes, Ray Leatherwood, and me. Then we did a third album with Betty O'Hara on various horns. She's something of a virtuoso on trumpet and trombone."

After the third album Magnagraphic went out of business, but now the door was open, and Johnny moved on to making more records. For the Fairmount label he did Johnny Varro at the Piano accompanied by Gene Estes and bassist Leroy Vinegar. Then came Portrait in Jazz, with Buzzy Drootin. and Dave Stone. This was originally produced by Wayne Rice, who died shortly after, and as a result "just lay there," as Johnny puts it, until Floyd Levin volunteered to release it on his Artistry label.

In 1986 Johnny was tapped to tour Europe with a band lead by Wild Bill Davison. Others in the group included Tom Saunders, second cornet, Chuck Hedges, trombonist Bill Allred, Butch Miles on drums, and English tenorman Danny Moss, along with a Swiss bass player, Isla Eckinger. Banu Gibson was the vocalist.

"We recorded with that band in Germany, and it was a helluva album, but something happened to it. I don't know just what, but I do know that Ann Davison is trying to get it. I can't talk too much about it because I'm not really aware of what took place. I have a tape of it, so I know it's really good, and when it was originally reviewed it got five stars.

Three top keyboard artists in Odessa, Texas, 1989. From left, Johnny Varro, Ralph Sutton, Ray Sherman. |

"I made another album in Germany with Christian Plattner. It's a pretty good record, with Christian on tenor sax, a bass player named Tomas, and Butch Miles on drums. I also made an album with Peanuts Hucko, which they tell me has been released and is out there somewhere. In Europe, I guess, although I really don't know where the hell it is. Of late I've been doing a lot of recording for Mat Domber, who produces Arbors Records, and George Buck has released a series of CDs recorded live at the Atlanta Jazz Festival. Three of them were released as Ed Polcer's All Stars on the Jazzology label, and one, under the name of Allan Vaché-Johnny Varro Combos, is on Audiophile. They're all good.

"I'll be rejoining Allan in August of this year and were going to Germany to play and record for Sabina Nagel-Heyer. She produced the CD called A Tribute to Eddie Condon that we made a year or so ago with the band Ed Polcer took over on tour. Besides Eddie and Allan it included Bob Havens on trombone, two Englishmen, John Barnes on baritone sax, and Jim Douglas, guitar, Bob Haggart and Butch Miles. This time I understand that Warren Vaché, Jr. will join us for this session, so it should be very interesting.

"So as you see, I'm making up for lost time on recordings. I have quite a slew of them around now, and I'm pretty happy about it. It's the only way a musician can build a reputation these days.

"What are my plans for the future? Well, I've put together a seven-piece band I call The Swing Seven. This goes back to something I began doing while I was still in California. I used to teach at a jazz camp outside of Sacramento. They'd bring us in and we'd work with the kids, try to make them understand what jazz is all about, how to play, and how to improvise. A lot of times the kids were incapable of improvising, so I started writing little arrangements, little things to incite them into wanting to play, and how it is to blend the voices of instruments. Writing for them got me started in writing for myself, and for the past two years I've been writing for a seven-piece band.

"We do some of John Kirby's numbers, although I feature seven men where he had six. He used trumpet, clarinet and alto. I'm using trumpet, trombone, clarinet and tenor. The sound is a little heavier. We played our debut concert at `The Piano Spectacular' segment of the JVC-New Jersey Jazz Society festival at Waterloo Village. I had Randy Sandke, Phil Bodner, Harry Allen, Dan Barrett, Joe Ascione, and Frank Tate. This is quite a band, and I want to keep it working. We're doing some sessions at the Van Weisel Hall in Sarasota, and have got a tour lined up for October. So things are off to a good start."

Or to put it another way, Johnny Varro is at last coming into his own, both in person and on recordings. It's an encouraging indication that jazz is still being nurtured by capable hands.